Warning: This is a long, rambling post!

I enjoy knitting socks, but even the sturdiest socks eventually wear out. Roy's socks always wear through in the same spot--underneath the heel. I've tried reinforcement, but that just delays the inevitable. The sock yarn disappears, leaving a little network of reinforcement yarn. I do own a sock darner, but the results are always a little lumpy. And ugly. And I hate darning socks.

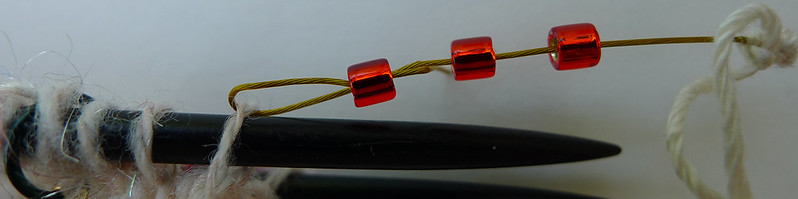

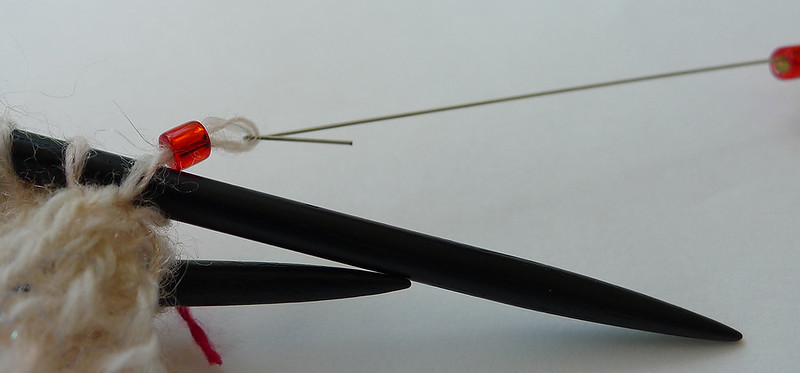

So, when Roy hands me a sad pair of holey handmades, my process goes something like this. I pick up the stitches on the top end and the foot end:

I cut between the needle sets to produce two halves...

...and then ravel the yarn back to the needles:

Snarky Aside: Notice the fresh and brilliant colors on these socks. That's because the Socks That Rock yarn gave out after about twenty wearings and washings. The faded sock you'll see later in this post was worn and washed for seven years before the lovely Fleece Artist yarn needed repair.

After knitting a new gusset and heel, I used Kitchener Stitch (KS) to connect the two halves together. It takes more time to KS than to re-knit the entire midsection, and frankly, Kitchener Stitch is not my favorite thing to do. No matter how careful I am, one or two of 60-odd stitches is always wrong. No, I am not showing you any pictures of that.

So today I started fiddling around with an odd idea. For some time, I have been longing to make the Paton's Cable Yoke sweater. The lovely example shown below was knitted by Tanis of Tanis Fiber Arts (photo used with permission).

The sweater is constructed by first knitting the strip of cable for the yoke, which is then grafted together to form a circle. The upper and lower parts of the sweater are picked up from the edges of the cable strip.

My thought process then drifted over to the idea of knitted-on lace edgings. For those of you who have never done this, you basically turn your work 90 degrees and cast on for the edging. You knit to the end of the edging, turn, and knit back towards the shawl body. Then you knit the last stitch of the edging together with a stitch on the shawl. Repeat a million times until all the stitches are gone or you have stuffed the thing into the deepest, darkest closet you own, hoping the shawl will dissolve so you don't have to knit any more edging.

So, I thought to myself...what if I started knitting the Paton's sweater from the neck and knit down to the yoke, leaving the live stitches on the needle? Then do a provisional cast-on for the lower body and finish that section. I will have two sets of live stitches that I can join at each edge of the cable strip, which is knitted sideways.

This process would be essentially the same as joining two sock halves with a knitted band instead of Kitchener Stitch.

I found an old sock that needed repair to experiment. After I finished the gusset and heel section, I turned it 90 degrees and cast on four stitches using the Knitted Cast On. Because I had to turn the work to the wrong side to cast on, I actually used the Purled Cast On, which consisted of making a purl stitch in the last stitch on the needle, putting the stitch on the needle, then purling in that stitch, and so on. I purled (through the back loops) the final cast-on stitch with one stitch from the upper sock half, which made a tight join.

I turned the work and slipped the first stitch, knit the two stitches in the center of the strip, then knit one stitch of the strip with one stitch of the heel half through the back loops. Continue turning and working, or do as I do and knit backwards to save time and trouble. Always slip the first stitch, which is the decrease from the previous row. And pull that slipped stitch tight to prevent a hole.

When I got to the end, I picked up four stitches from the beginning and Kitchenered them together with the four left on the needle. If I had been picky, I could have done a provisional cast on at the start, but for such a small number of stitches, it wasn't worth the trouble. Fours stitches of KS is a lot better than 60.

I used four stitches so I could observe the process better, but it seemed to me that the extra two stitches in the center weren't necessary for the sock join.*

In the next example, I cast two stitches onto the right needle by knitting on backwards, slipped the final stitch to the left needle and knit it together with one stitch from the ribbing half of the sock. Then I slipped that stitch, and knit the next stitch together with one stitch from the heel half. I continued in this way, slipping the first stitch and knitting (or purling) the last stitch of the heel half together with one stitch on the top half. The result is a pretty little braided effect that's smooth on the inside:

I only had to KS two stitches at the end--even better!

This technique can be used to join any set of live stitches, for example, afghan squares, and will hopefully inspire some interesting designs using pretty insertions. The join can be used to replace the bulky and inflexible three-needle bind-off too. The result is very stretchy, but because it stretches perpendicularly to the joined pieces, you don't have to worry about sagging if you are using a heavy yarn. Finally, the join can be as wide as you like and pretty much any stitch can be used for the join, for example, purls, garter stitch, lace, or fancy braided cables.

* I know. Some of you are wondering why I bothered to reknit the gusset and heel on that sad, washed-out sock. It's because the sock yarn has cashmere in it and these little treasures are indefinably soft and sqooshy. You can see how the color has faded over the last seven years, but now they are ready to go for another seven, just like me! Too bad I can't just unravel my failing bits and re-knit them, sigh.

Sunday, November 4, 2012

Friday, October 12, 2012

Vostok

About five years ago, I bought some qiviut yarn from a now-forgotten vendor. I hated it. It wasn't anywhere near as soft as advertised, had as much stretch as garden twine, and somehow still warped out of shape after knitting. For the price, I could have bought some cheap acrylic and gotten the same amount of satisfaction.

While I was writing Fleegle Spins Supported, I purchased some unspun qiviut roving from Cottage Craft Angora...and boy, did my opinion of this stuff skid into a complete, 180-degree turnaround. The roving is a dream to spin, dyes beautifully, and knits up into a delicate, luxurious fabric that is difficult to stop touching.

Here's the roving, the spun yarn on a supported Trindle, and the final yarn, dyed a rich, dark purple.

From the admittedly costly and indulgent two ounces I purchased, I ended up with 900 yards of laceweight two-ply, and decided to knit Vostok, an exquisite design by Beth Kling. I used a size 3 needle, and had about 150 yards left over.

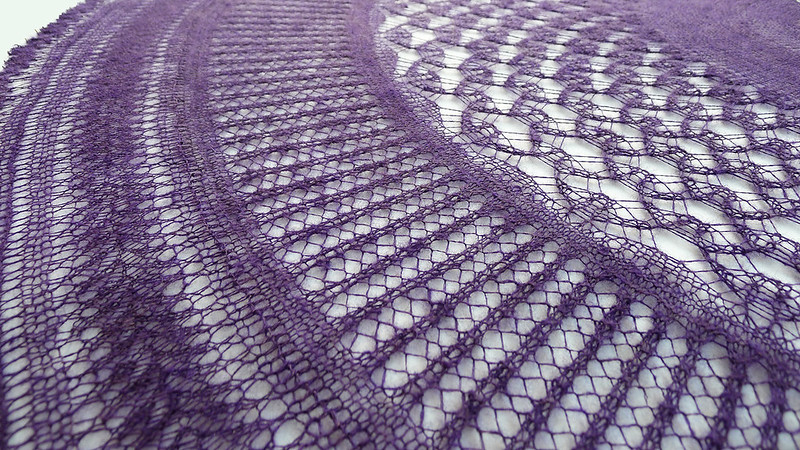

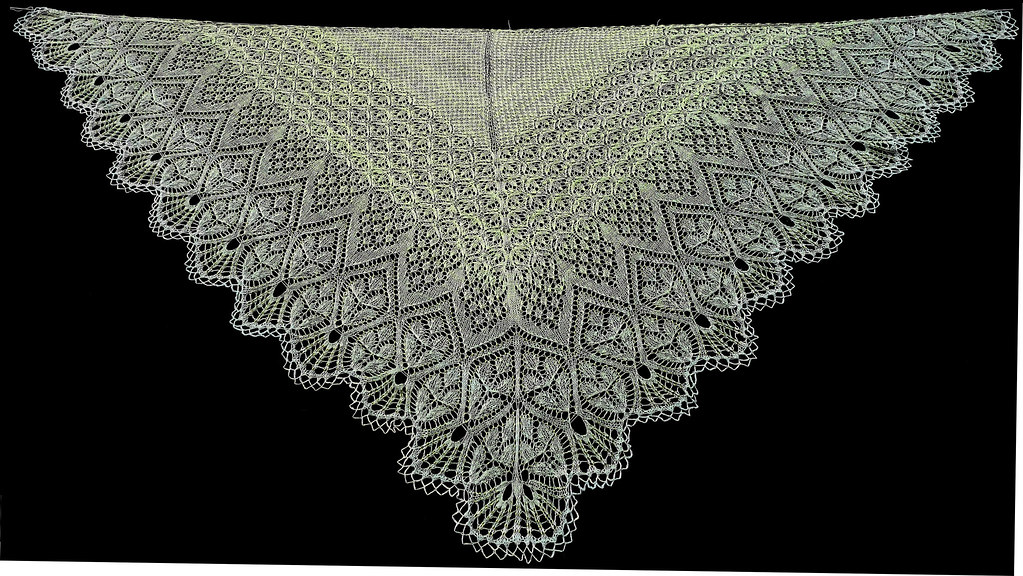

As you can see, the shawl consists of bands of ethereal lace, all of which are patterned on both sides.

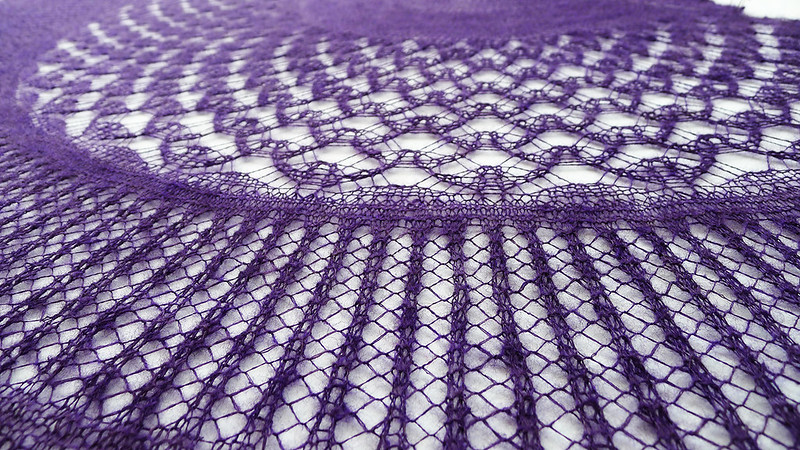

I like semi-circular shawls, because they don't slide off your shoulders like triangular ones do. I was, however, bothered by the neck area, which seemed insubstantial. The shawl hangs from the cast-on edge, and that made me uneasy. And when I tried on the shawl, the neck just looked unfinished.

After consulting my library of crochet patterns, I decided to add a small collar. You can see it in the first photo--it's the odd thingie sticking up at the top of the shawl.

And here's what it looks like when worn:

And from the back:

I hadn't crocheted lace in a long time, but it didn't take long and I think the result is visually pleasing. I will be adding a similar collar to my Nouveau Beaded Capelet to give the neck a bit of body. That's a heavy shawl and a little collar will add strength, as well as a bit of interest to the neck area.

While I was writing Fleegle Spins Supported, I purchased some unspun qiviut roving from Cottage Craft Angora...and boy, did my opinion of this stuff skid into a complete, 180-degree turnaround. The roving is a dream to spin, dyes beautifully, and knits up into a delicate, luxurious fabric that is difficult to stop touching.

Here's the roving, the spun yarn on a supported Trindle, and the final yarn, dyed a rich, dark purple.

From the admittedly costly and indulgent two ounces I purchased, I ended up with 900 yards of laceweight two-ply, and decided to knit Vostok, an exquisite design by Beth Kling. I used a size 3 needle, and had about 150 yards left over.

As you can see, the shawl consists of bands of ethereal lace, all of which are patterned on both sides.

I like semi-circular shawls, because they don't slide off your shoulders like triangular ones do. I was, however, bothered by the neck area, which seemed insubstantial. The shawl hangs from the cast-on edge, and that made me uneasy. And when I tried on the shawl, the neck just looked unfinished.

After consulting my library of crochet patterns, I decided to add a small collar. You can see it in the first photo--it's the odd thingie sticking up at the top of the shawl.

And here's what it looks like when worn:

And from the back:

I hadn't crocheted lace in a long time, but it didn't take long and I think the result is visually pleasing. I will be adding a similar collar to my Nouveau Beaded Capelet to give the neck a bit of body. That's a heavy shawl and a little collar will add strength, as well as a bit of interest to the neck area.

Monday, September 3, 2012

Echobellinaria

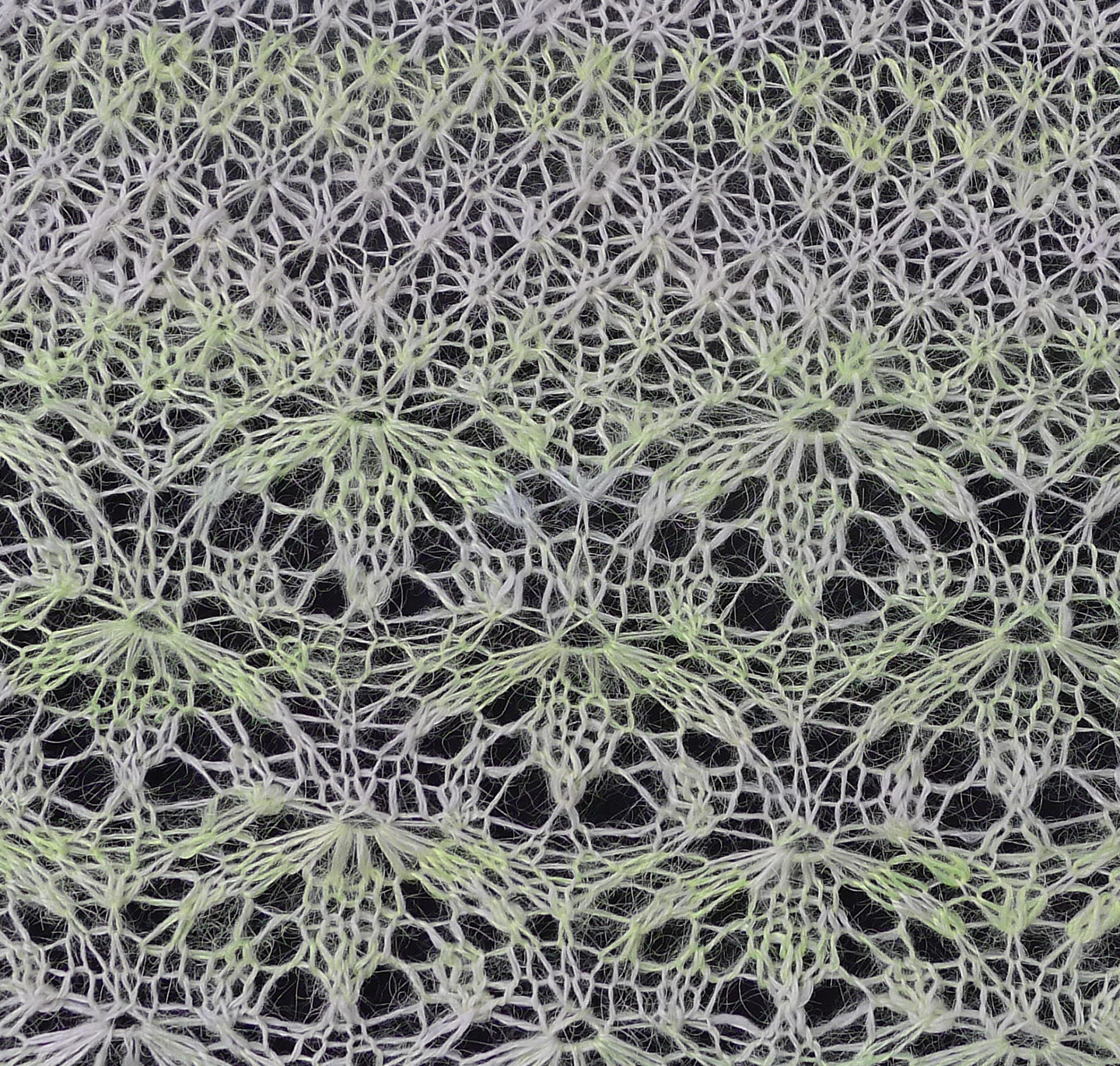

My Echobellinaria shawl started out innocently enough as Melissa Lemmon's lovely Silver Bells and Cockleshells. I had a ball of handspun laceweight--1400 yards--and the requisite 1000 beads for the border and figured I would just mindlessly zone out through the tedious number of small motifs in the top section. It would, I told myself, be worth it to endure a bit of boredom because of that truly stunning border.

I cast on on with size 4 needles and knit the setup…realized that was too big a needle, switched to size 3, knit the setup…too big, cast on a with size 2. That looked nice, but after two repeats of the pattern, I tossed down the needles with a huge sigh. There was no way I was going to knit miles of those little diamond thingies and Harry had scuttled away after watching me play musical needles for an hour.

I perused my Ravelry Favorites, and decided to work a pretty little mashup composed of several patterns. I would knit some repeats of Laminaria, then some repeats of Echo Flowers, and finish up with the lovely border on Silver Bells. For the most part, the stitch counts in the three sections were perfectly compatible and required very little fudging to make it work.

My Post-It note, which detailed the concept, read:

Laminaria star chart and transition chart

Echo Flowers chart

Silver Bells and Cockleshells edging

I cast on with a size 2 and knit the Laminaria setup…hmm, too small a needle. Tried again on a size 3, and again on a size 4, and yet again on a size 5. That looks nice. By this time, my herd of knitting needles was cautiously edging away from me. You could hear them mumbling about people who couldn't make up their minds and piled up rejects without regard to order, decorum, or dignity.

Off we go. Knit the first repeat. Holy Merlin! That was the UGLIEST center stitch I have ever seen! Ripped it out and tried a few things for the center stitch…until I realized that a plain knit just continued the pattern and didn’t leave much of a backbone.

I figured five repeats would be enough, but it looked a bit mingy, so I knit two more repeats before proceeded onto the transition chart, and then the Echo Flowers pattern. Plenty of yarn left, so I did seven repeats of this pattern, too.

The Echo Flowers repeat is 12 stitches and the Silver Bells edging repeat is

24 stitches, but I had to flim-flam away 12 extra stitches to make the border pattern

work out correctly. On the outer edge, I decreased away 3 stitches on the first row. At the center, I omitted the increases until the stitch count caught up to the pattern.

As I was blithely knitting away, popping on beads with abandon, I turned to the final pattern page and noticed that there were a slew of 1 to 16 stitches increases on the last part of the border. The double set of crocheted loops was really going eat up the yarn, too. I needed to spin more yarn. A lot more.

After I found some matching fiber, I eyeballed my diminishing bead supply. As I mentioned in my last blog post, every single tube of beads I own has a stock number and supplier neatly printed on a small label...except the ones I was using. It took me two weeks to figure out where I had gotten them, then I called the store and had them send me two more tubes.

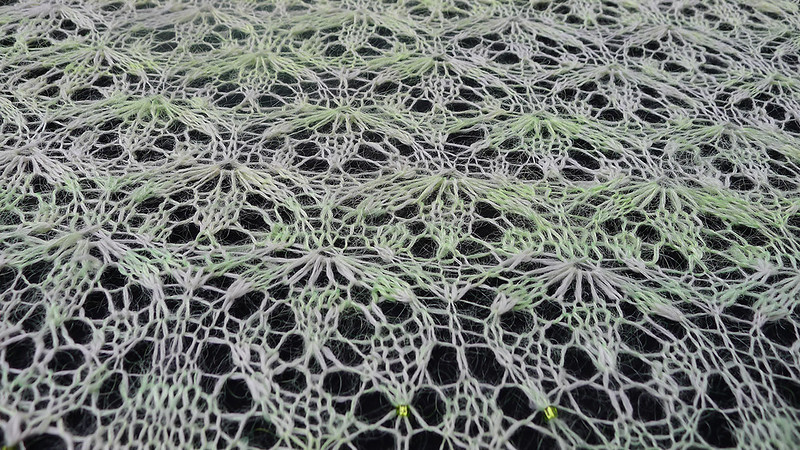

By the time I arrived at the truly lovely edging, my pretty little shawl had mutated into a blanket/car cover...I mean, I should have had some idea that things were getting out of hand when I used up the 1400 yards in the original ball about a third of the way into the border.

Be that as it may, the final piece measures 96" across the top and 54 inches deep...sufficient to keep any two people or a station wagon warm on a cold day.

The lovely color gradient isn't apparent when the shawl is lying flat, but you can see it in this photo:

If I were going to knit it again (fat chance), I would go with five repeats each of Laminaria and Echo Flowers. It would still be a large undertaking, but I probably could have completed it with the original yarn and beads.

As I was blithely knitting away, popping on beads with abandon, I turned to the final pattern page and noticed that there were a slew of 1 to 16 stitches increases on the last part of the border. The double set of crocheted loops was really going eat up the yarn, too. I needed to spin more yarn. A lot more.

After I found some matching fiber, I eyeballed my diminishing bead supply. As I mentioned in my last blog post, every single tube of beads I own has a stock number and supplier neatly printed on a small label...except the ones I was using. It took me two weeks to figure out where I had gotten them, then I called the store and had them send me two more tubes.

By the time I arrived at the truly lovely edging, my pretty little shawl had mutated into a blanket/car cover...I mean, I should have had some idea that things were getting out of hand when I used up the 1400 yards in the original ball about a third of the way into the border.

Be that as it may, the final piece measures 96" across the top and 54 inches deep...sufficient to keep any two people or a station wagon warm on a cold day.

The lovely color gradient isn't apparent when the shawl is lying flat, but you can see it in this photo:

If I were going to knit it again (fat chance), I would go with five repeats each of Laminaria and Echo Flowers. It would still be a large undertaking, but I probably could have completed it with the original yarn and beads.

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Two Tweaks

My latest project, Echobellinaria, is an fascinating mashup of Laminaria, Echo Flowers Shawl, and Silver Bells and Cockleshells, knitted with handspun merino silk. Alas, the ubiquitous, obnoxious Murphy showed up in my kitchen while I was on the home stretch. I ran out of both yarn and beads twenty rows from the end. I spun more yarn, but have had the darnedest time trying to find matching beads. All of my bead tubes sport labels with both the company name and bead number, except, of course, the tubes I decided to use for this shawl.

I finally remembered where I purchased them, and called the store yesterday. I'm hoping against hope that they are a good match, because the other three tubes I ordered from various web stores weren't.

fleegle hands Murphy a cup of coffee laced with the Draught of Living Death and gleefully watches him drink it down....

In the meantime, I thought I would post two quick tweaks for improving efficiency. If you don't spin or bead, well, stay tuned for the next post, which will hopefully be replete with Echobellinaria eye candy.

Spindle Shafts

I have small fingers, and find twirling spindles with thick shafts very difficult and tiring. If you are experiencing the same problem, try sanding down the top of the shaft. For me, reducing the shaft diameter from the one shown on the left to more svelte version on the right makes for a miraculous improvement in spindle efficiency. Give it a whirl, as it were.

Use a piece of 220 grit sandpaper about 2 inches wide to quickly reduce the diameter of the upper two inches or so. When you get close to the final diameter, go down to 600 grit, using a piece about 1 inch wide.

Be careful to revolve the spindle as you sand so the shaft remains round and true.

For the final polish, use 800 grit, about 1 inch wide. Some people might want to wax the sanded area or use wood polish, but I haven't found it necessary.

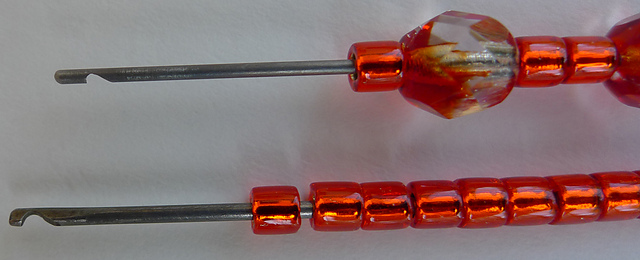

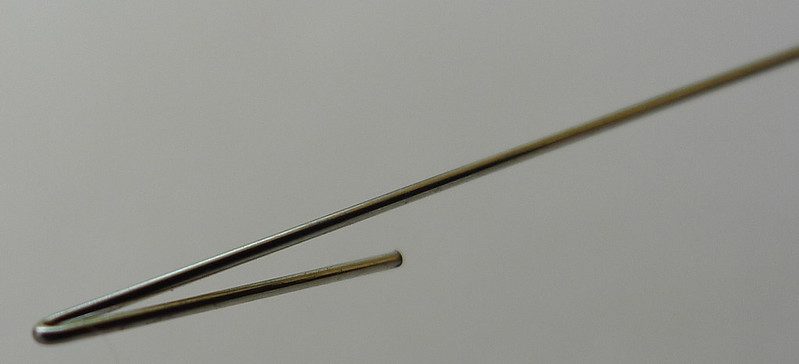

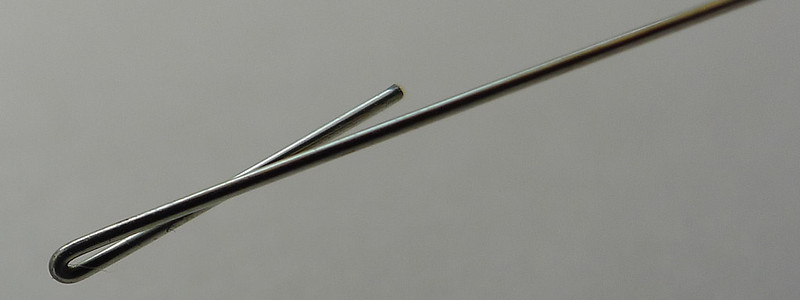

Beader Tweak

I was hesitant to post this, but figured someone might be adventurous and try it. The other day I was fitting the caps onto my beaders, and I accidentally bent the tip on one of the 0.8mm beaders about five degrees. I couldn't sell it, so I set it aside for me. I used it this morning, and found it to be a huge improvement. The slight bend forced the yarn to slide right into the slot. Here's a photo:

I grabbed another beader and used the cap to bend it VERY GENTLY...and it worked splendidly.

I finally remembered where I purchased them, and called the store yesterday. I'm hoping against hope that they are a good match, because the other three tubes I ordered from various web stores weren't.

fleegle hands Murphy a cup of coffee laced with the Draught of Living Death and gleefully watches him drink it down....

In the meantime, I thought I would post two quick tweaks for improving efficiency. If you don't spin or bead, well, stay tuned for the next post, which will hopefully be replete with Echobellinaria eye candy.

Spindle Shafts

I have small fingers, and find twirling spindles with thick shafts very difficult and tiring. If you are experiencing the same problem, try sanding down the top of the shaft. For me, reducing the shaft diameter from the one shown on the left to more svelte version on the right makes for a miraculous improvement in spindle efficiency. Give it a whirl, as it were.

Use a piece of 220 grit sandpaper about 2 inches wide to quickly reduce the diameter of the upper two inches or so. When you get close to the final diameter, go down to 600 grit, using a piece about 1 inch wide.

Be careful to revolve the spindle as you sand so the shaft remains round and true.

For the final polish, use 800 grit, about 1 inch wide. Some people might want to wax the sanded area or use wood polish, but I haven't found it necessary.

Beader Tweak

I was hesitant to post this, but figured someone might be adventurous and try it. The other day I was fitting the caps onto my beaders, and I accidentally bent the tip on one of the 0.8mm beaders about five degrees. I couldn't sell it, so I set it aside for me. I used it this morning, and found it to be a huge improvement. The slight bend forced the yarn to slide right into the slot. Here's a photo:

I grabbed another beader and used the cap to bend it VERY GENTLY...and it worked splendidly.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

A Billion Beads, Redux

Harry returned home a few weeks ago from his wild and wacky vacation at the Blur Bowling Ally in Tirana, Albania. If you click the link and watch the live webcam, look for his condo--a black box at about 1:00. Note the little stage at the top, where he entertained the bowlers with his newest gig--Gangsta Rap Noh, a tasteful blend of contemporary stylistic repartee and traditional Japanese dance. Frankly, I think a bowling alley is the perfect spot for his performance...the crash of falling pins is a lovely accompaniment to his, um, singing.

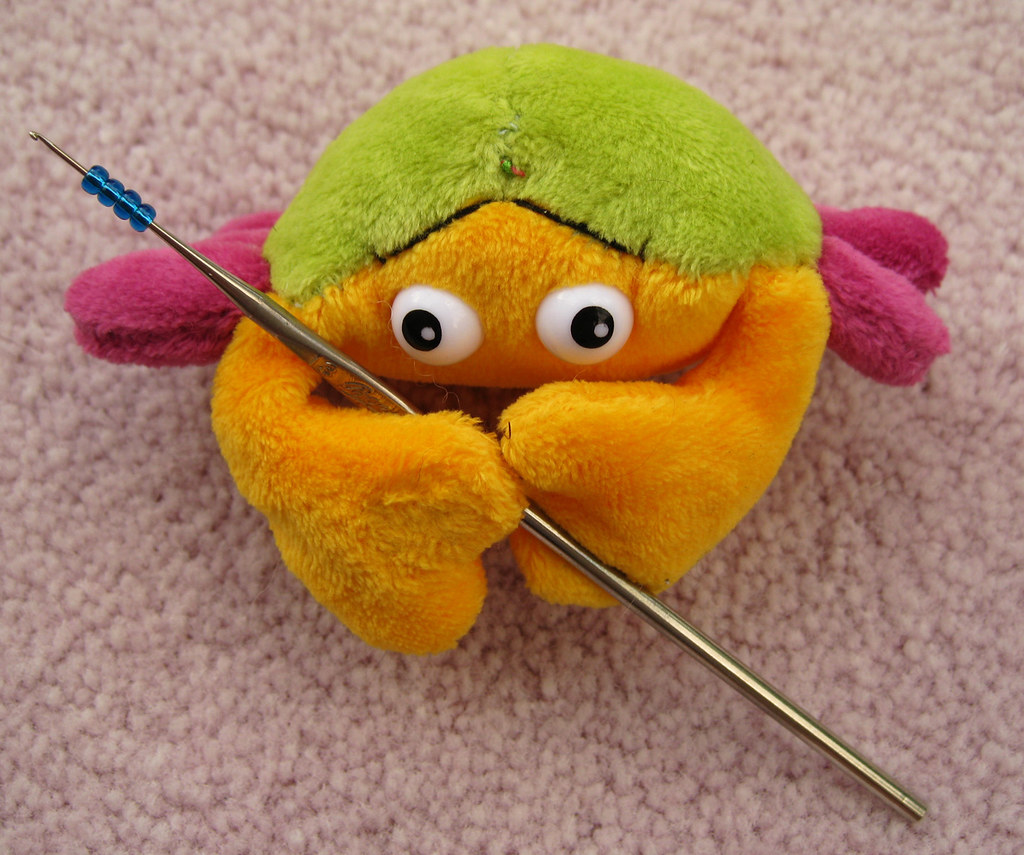

While he was resting, Harry spent his time working for my Etsy shop, The Gossamer Web. From a passing bowler, Harry managed to obtain some spring steel, a couple of files, and enough goat cheese to stock his pantry. The result: The Fleegle Beader, our answer to the crochet hook-floss threader-wire methods of adding beads to your knitting. (Sorry, Harry ate the goat cheese.)

After considerable debate, we decided to name it The Fleegle Beader, because I pointed out that The Harry Beader sounded ridiculous. However, Harry does star, along with other members of his extensive family, in the Ravelry ad. It took most of the day to get everyone lined up on the supersized beader handle, but we thought the ad turned out pretty well.

These beaders are available in two sizes.

The 0.8mm size is for designed #8 and #11 seed beads. It will hold about 60 #8 or 90 #11 beads. The picture below shows a mixture of #8 and 6mm faceted Czech glass beads with teeny, tiny holes. I like to use these beads as nupp replacements.

The 1.0mm size is designed for #6 or #8 beads with large holes, such as Delicas. It will hold about 60 #8 Delicas--my favorite bead for knitting.

The tip has a hook that will work with yarn as thick as heavy fingering weight.

The bottom of the beader is bent so you can use it with a bead spinner. Comes with a tip protector and two stoppers for the bottom, because you might lose one and I don't want you to be unhappy.

While he was resting, Harry spent his time working for my Etsy shop, The Gossamer Web. From a passing bowler, Harry managed to obtain some spring steel, a couple of files, and enough goat cheese to stock his pantry. The result: The Fleegle Beader, our answer to the crochet hook-floss threader-wire methods of adding beads to your knitting. (Sorry, Harry ate the goat cheese.)

After considerable debate, we decided to name it The Fleegle Beader, because I pointed out that The Harry Beader sounded ridiculous. However, Harry does star, along with other members of his extensive family, in the Ravelry ad. It took most of the day to get everyone lined up on the supersized beader handle, but we thought the ad turned out pretty well.

These beaders are available in two sizes.

The 0.8mm size is for designed #8 and #11 seed beads. It will hold about 60 #8 or 90 #11 beads. The picture below shows a mixture of #8 and 6mm faceted Czech glass beads with teeny, tiny holes. I like to use these beads as nupp replacements.

The 1.0mm size is designed for #6 or #8 beads with large holes, such as Delicas. It will hold about 60 #8 Delicas--my favorite bead for knitting.

The tip has a hook that will work with yarn as thick as heavy fingering weight.

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Bear with Me...

Life Lesson # 4545: Beware of anyone bearing a large, orange Home Depot pail and a really big grin. Although he ostensibly went for a walk in the woods, somehow Roy returned home with about two pounds of, um, grizzly bear fur.

His story (verbatim):

I was walking in the forest, when all of a sudden, a huge, ferocious, mean, nasty, scary grizzly bear leapt out of the trees, intent on stealing my fruit bar. We wrestled for a while, and after a few right hooks and an uppercut to his snout, I forced him onto the ground and held him down in a hammerlock. Knowing how much you love exotic fiber, I whipped out my trusty comb, ran it through his/her pelt, and collected the fur in this handy orange pail that I always take camping, because you never know when you'll need one.

The real story, needless to say, revolved around the nearby bear park, a kind manager, and the same orange pail...

Never having gotten close enough to a bear to run my fingers through its fur, I was prepared for just about anything. My sense, from looking at bears from a respectfully healthy distance, is that the fur would be rather coarse. And I was right.

Not surprisingly, bears shed in the summer months. The fur is a mixture of long hairs and a reasonably soft undercoat. We washed it gently in a bit of detergent, the rinsed it and let it dry in a mesh bag overnight.

I spent an hour with a fine-toothed comb and removed the outer hairs, leaving a handful of springy short fur that felt quite like Shetland wool. And like wool, bear fur is well lubricated, containing a healthy amount of, um, bear oil?

I didn't think that spinning the undiluted fur would be rewarding, so I grabbed a bit of merino/silk, and carded it with the bear fiber. The ratio was about 30% grizzly, 70% merino/silk.

Then I grabbed a Tibetan supported spindle and spun it into a single, two plies of which will make a fingering weight yarn.

This stuff is surprisingly pleasant to spin--springy and not the least bit slippery, thanks to the natural oils. It was easy to pluck out the remaining coarse hairs, producing a lively yarn which, while not luxuriously soft, would make interesting outerwear. And Roy, after his death-defying escapade, certainly deserves an ear warmer made from handspun merino/silk/grizzly bear.

The fur was donated by Mikie, a Rocky Mountain Grizzy, ten feet tall, weighing in at a svelte 1000 pounds. Mikie's day job is acting; he starred in Budwiser commercials in 1997 and 1998. No, I don't know what he was doing with the beer. Probably eating the cans whole.

His story (verbatim):

I was walking in the forest, when all of a sudden, a huge, ferocious, mean, nasty, scary grizzly bear leapt out of the trees, intent on stealing my fruit bar. We wrestled for a while, and after a few right hooks and an uppercut to his snout, I forced him onto the ground and held him down in a hammerlock. Knowing how much you love exotic fiber, I whipped out my trusty comb, ran it through his/her pelt, and collected the fur in this handy orange pail that I always take camping, because you never know when you'll need one.

The real story, needless to say, revolved around the nearby bear park, a kind manager, and the same orange pail...

Never having gotten close enough to a bear to run my fingers through its fur, I was prepared for just about anything. My sense, from looking at bears from a respectfully healthy distance, is that the fur would be rather coarse. And I was right.

Not surprisingly, bears shed in the summer months. The fur is a mixture of long hairs and a reasonably soft undercoat. We washed it gently in a bit of detergent, the rinsed it and let it dry in a mesh bag overnight.

Raw grizzly bear fiber

I spent an hour with a fine-toothed comb and removed the outer hairs, leaving a handful of springy short fur that felt quite like Shetland wool. And like wool, bear fur is well lubricated, containing a healthy amount of, um, bear oil?

Dehaired grizzly bear fiber

I didn't think that spinning the undiluted fur would be rewarding, so I grabbed a bit of merino/silk, and carded it with the bear fiber. The ratio was about 30% grizzly, 70% merino/silk.

Grizzly bear fiber carded with merino/silk

Grizzly bear fiber and merino/silk rolag

Then I grabbed a Tibetan supported spindle and spun it into a single, two plies of which will make a fingering weight yarn.

Grizzly bear fiber and merino/silk, spun on a supported spindle

This stuff is surprisingly pleasant to spin--springy and not the least bit slippery, thanks to the natural oils. It was easy to pluck out the remaining coarse hairs, producing a lively yarn which, while not luxuriously soft, would make interesting outerwear. And Roy, after his death-defying escapade, certainly deserves an ear warmer made from handspun merino/silk/grizzly bear.

The fur was donated by Mikie, a Rocky Mountain Grizzy, ten feet tall, weighing in at a svelte 1000 pounds. Mikie's day job is acting; he starred in Budwiser commercials in 1997 and 1998. No, I don't know what he was doing with the beer. Probably eating the cans whole.

Sunday, May 27, 2012

A Billion More Beads...

A while back, I wrote a post about making a more efficient beading crochet hook by gently applying a Dremel to the shaft of a crochet hook:

I was happier with the edited hook...but not ecstatic....6000 divided by 12 beads per load is (scribble scribble) 500 bead loads. The hook is heavy, so it can't be parked on the knitting itself. Worse, the only place to put it while knitting non-beaded stitches is in my mouth (tastes, um, beady?) or on the table (rolls around, beads slide off the hook). It was a better solution than a regular crochet hook, but not the ultimate one.

With my usual impeccable sense of timing, I started thinking seriously about more efficient beading methods after finishing the capelet. I have gathered here all the tools and techniques I could find, and present you with the options, complete with photos andsnarky pithy commentary.

Crochet Hook

The tiny crochet hook is probably the most common method of adding beads to your knitting. You put a bead on the hook, snag the stitch, and pop on the bead:

An ordinary crochet hook can hold about four or five beads, which means you have to reload fairly often. Sanding down the shaft can increase your, um, bead magazine to about a dozen or so, but for something like the capelet, the crochet hook is wildly inefficient.

Also, the nature of a hook means that it's a bit bulky, so you have to use a tiny size (US #11-14 or so) to ensure that the hook can fit through the bead hole. A miniscule hook can often present an unhappy experience with heavier laceweight yarn by grabbing part of the yarn, separating plies, and can also inadvertently break fibers.

Crochet hooks are easy to find, though, and you can also use them to crochet and fish tiny objects out of crevices.

Dental Floss Threaders

The concept is excellent. There's a stiff end for threading and a foamy section on which the beads rest comfortably without sliding. You can string a lot of beads onto these and use the extras to floss your teeth or tie up tomato plants. Threaders are cheap and readily available at any store that carries dentalware.

You insert the stiffened tip through the stitch, pinch the threader closed, and slide the bead over the tip and the yarn thusly:

I don't like using floss threaders, because the tip isn't very stiff, so pinching it closed feels awkward for me. Adding beads can be tedious, too, as it can't be used with a bead spinner. The tip is straight, so it can't be easily parked on the knitting.

On the plus side, threaders are lightweight and can be flopped over your arm or around your glasses.Or you can floss and leave it between your teeth until you reach another beading stitch. Your dentist will be so proud of your sparkly clean molars!

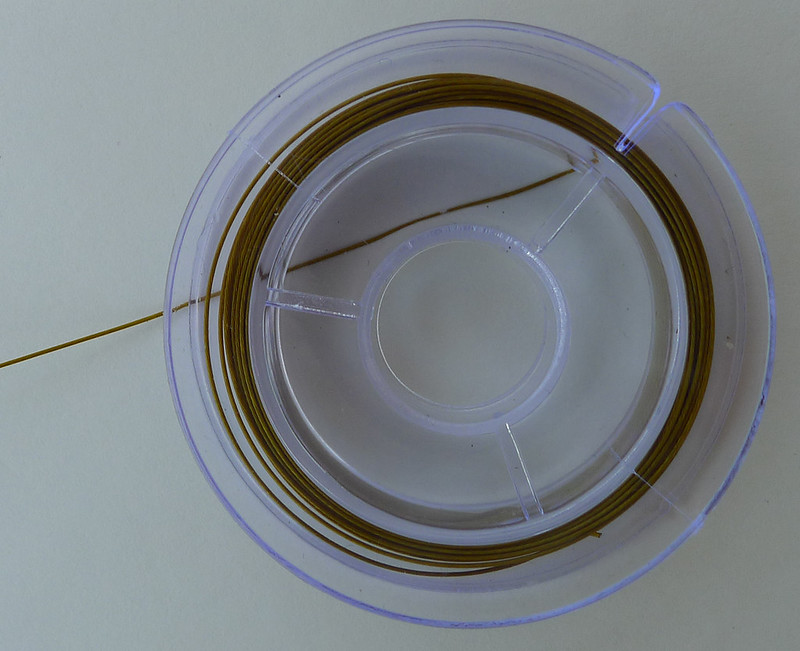

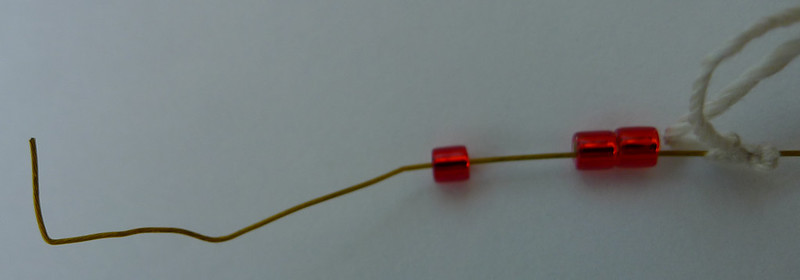

Beading Wire

I read about this technique on Melissa Lemon's blog (she's the Nouveau Capelet designer). It's the same concept as the floss threader, but uses nylon-coated, .015″/.38mm Tiger Tail, which is a flexible, braided stainless steel, nylon-coated wire. It's very cheap and available in almost every bead store.

Just cut the wire to the desired length and tie a bead on the non-working end or make a knot to prevent the beads from sliding off. Then make a hook on the working end by folding about a inch of the wire back on itself.

To use the wire, hook the folded section into the stitch, pinch it together with the main section, and slide the bead onto the stitch:

Beading wire is lightweight and has a hook section that can be parked directly on your knitting. You can thread a zillion beads onto the wire, although be warned, cats think a string of beads is a really fun thing to play with. It wiggles and makes a nice clicky sound when whapped with a paw.

On the downside, the wire isn't stiff enough to use with a bead spinner, and its flexibility makes it it difficult to pinch the hook. Any re-bends you make never straighten out, so eventually, you end up with a wiggly hook...

You can cut off the messy ends to make a clean fold, which eventually leads to a short piece of wire capable of holding a single bead...so you have to make another one.

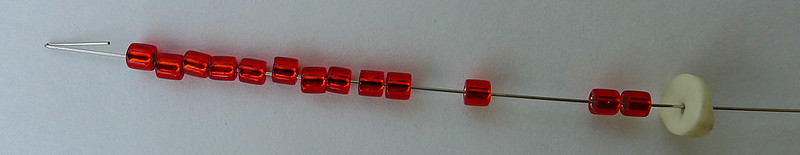

Lacis Verna Beadle Needle

I saw this on Lacis's website and had to have one. The description made it sound like the ultimate, perfect, beaded knitting solution. The Beadle is billed as an eight-inch length of tempered steel with two rubber stoppers, a hook on one end, and a bent section on the other to allow it to be used with a bead spinner. There are several sizes; the one I purchased can hold about 100 beads:

Alas, the description is misleading. There's no hook. Instead, there's kind of a notch:

The notch on the first one I received was so shallow that the yarn just slid right off of it. I used a file to deepen the notch, which made it work well with cobweb weight, but heavier standard laceweight didn't catch in the notch. Jules kindly send me a replacement, which was a little better, but it tends to grab one ply of the yarn and shred it if I forced the issue.

My replacement lacked the bend at the other end for the bead spinner, but it was easy to make a gentle curve with my fingers. However, I found the Beadle too long to be comfortable, and it can only be parked on a table or in your mouth. You have to use the rubber stoppers to prevent the beads from sliding off both ends. No big deal, but the second thing I did after I unpacked the little guy was lose one of the stoppers. They are small, round, and black, so they cheerfully roll under refrigerators and/or hide invisibly in the shadows around your floorspace.

The beadle is also expensive--about $15 without Lacis's, um, handling fee. It's a clever idea and with a little work on the notch/hook, the Beadle could be a pleasantly viable beading solution.

Guitar Wire

I read about using guitar wire instead of a floss threader years ago, but the recommended wire was a size 30, which is actually a wrapped core. I tried using this, but the finer wire wrapping invariably started unwrapping...

And it was too thick and and difficult to bend, at least for my beads and fingers.

Not to be discouraged, I revisited the guitar wire concept, and found that size 14, a thin, springy, wire, works much better for me. It's thin enough to accommodate every bead size, resilient enough to resist bending, pleasantly lightweight, and won't roll away.

I cut off a comfortable section and used a bead spinner to whirl a bunch of beads onto the non-hook end. No need to make a bend in the wire--it's springy and conforms comfortably to the spinner bowl.

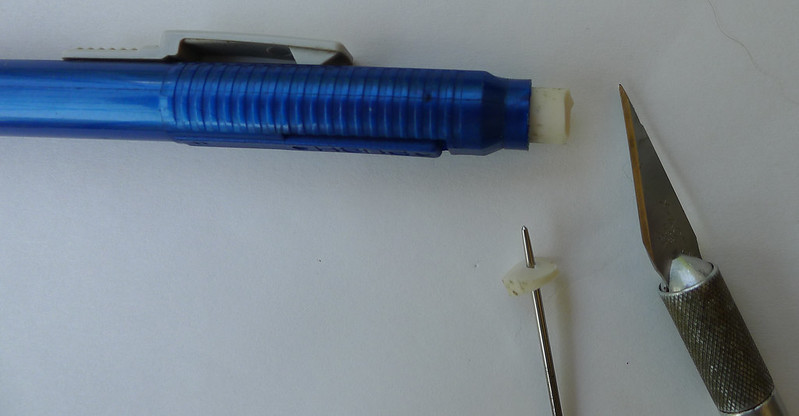

I took a pair of pliers and bent the end into a hook thusly:

Notice that the hook is bent quite far, but from the side, it's open enough to slide in the yarn:

It's quite easy to close the gap by bending the main wire towards the hook--no need to pinch it closed. Furthermore, the guitar wire has several advantages over the other methods. First of all, like the beading wire, the guitar string can be hooked directly onto your knitting:

Because there's a slight bulge at the hook end, beads won't fall off that end:

Making stoppers for the other end is simple. Use a sharp matte knife, cut a few slices from an eraser stick. Then poke a hole through each one with a thickish sewing needle and just slide it onto the wire:

Both the Beadle and this thing (the Fleeger? The Bleeger? The Bleegle? The FleegleBeadle? The Guitar-Wire-with-Hook-and-Stopper? ) store nicely in thick plastic straws.

.

With my usual impeccable sense of timing, I started thinking seriously about more efficient beading methods after finishing the capelet. I have gathered here all the tools and techniques I could find, and present you with the options, complete with photos and

Crochet Hook

The tiny crochet hook is probably the most common method of adding beads to your knitting. You put a bead on the hook, snag the stitch, and pop on the bead:

An ordinary crochet hook can hold about four or five beads, which means you have to reload fairly often. Sanding down the shaft can increase your, um, bead magazine to about a dozen or so, but for something like the capelet, the crochet hook is wildly inefficient.

Also, the nature of a hook means that it's a bit bulky, so you have to use a tiny size (US #11-14 or so) to ensure that the hook can fit through the bead hole. A miniscule hook can often present an unhappy experience with heavier laceweight yarn by grabbing part of the yarn, separating plies, and can also inadvertently break fibers.

Crochet hooks are easy to find, though, and you can also use them to crochet and fish tiny objects out of crevices.

Dental Floss Threaders

The concept is excellent. There's a stiff end for threading and a foamy section on which the beads rest comfortably without sliding. You can string a lot of beads onto these and use the extras to floss your teeth or tie up tomato plants. Threaders are cheap and readily available at any store that carries dentalware.

You insert the stiffened tip through the stitch, pinch the threader closed, and slide the bead over the tip and the yarn thusly:

I don't like using floss threaders, because the tip isn't very stiff, so pinching it closed feels awkward for me. Adding beads can be tedious, too, as it can't be used with a bead spinner. The tip is straight, so it can't be easily parked on the knitting.

On the plus side, threaders are lightweight and can be flopped over your arm or around your glasses.Or you can floss and leave it between your teeth until you reach another beading stitch. Your dentist will be so proud of your sparkly clean molars!

Beading Wire

I read about this technique on Melissa Lemon's blog (she's the Nouveau Capelet designer). It's the same concept as the floss threader, but uses nylon-coated, .015″/.38mm Tiger Tail, which is a flexible, braided stainless steel, nylon-coated wire. It's very cheap and available in almost every bead store.

Just cut the wire to the desired length and tie a bead on the non-working end or make a knot to prevent the beads from sliding off. Then make a hook on the working end by folding about a inch of the wire back on itself.

To use the wire, hook the folded section into the stitch, pinch it together with the main section, and slide the bead onto the stitch:

Beading wire is lightweight and has a hook section that can be parked directly on your knitting. You can thread a zillion beads onto the wire, although be warned, cats think a string of beads is a really fun thing to play with. It wiggles and makes a nice clicky sound when whapped with a paw.

On the downside, the wire isn't stiff enough to use with a bead spinner, and its flexibility makes it it difficult to pinch the hook. Any re-bends you make never straighten out, so eventually, you end up with a wiggly hook...

You can cut off the messy ends to make a clean fold, which eventually leads to a short piece of wire capable of holding a single bead...so you have to make another one.

Lacis Verna Beadle Needle

I saw this on Lacis's website and had to have one. The description made it sound like the ultimate, perfect, beaded knitting solution. The Beadle is billed as an eight-inch length of tempered steel with two rubber stoppers, a hook on one end, and a bent section on the other to allow it to be used with a bead spinner. There are several sizes; the one I purchased can hold about 100 beads:

Alas, the description is misleading. There's no hook. Instead, there's kind of a notch:

The notch on the first one I received was so shallow that the yarn just slid right off of it. I used a file to deepen the notch, which made it work well with cobweb weight, but heavier standard laceweight didn't catch in the notch. Jules kindly send me a replacement, which was a little better, but it tends to grab one ply of the yarn and shred it if I forced the issue.

My replacement lacked the bend at the other end for the bead spinner, but it was easy to make a gentle curve with my fingers. However, I found the Beadle too long to be comfortable, and it can only be parked on a table or in your mouth. You have to use the rubber stoppers to prevent the beads from sliding off both ends. No big deal, but the second thing I did after I unpacked the little guy was lose one of the stoppers. They are small, round, and black, so they cheerfully roll under refrigerators and/or hide invisibly in the shadows around your floorspace.

The beadle is also expensive--about $15 without Lacis's, um, handling fee. It's a clever idea and with a little work on the notch/hook, the Beadle could be a pleasantly viable beading solution.

Guitar Wire

I read about using guitar wire instead of a floss threader years ago, but the recommended wire was a size 30, which is actually a wrapped core. I tried using this, but the finer wire wrapping invariably started unwrapping...

And it was too thick and and difficult to bend, at least for my beads and fingers.

Not to be discouraged, I revisited the guitar wire concept, and found that size 14, a thin, springy, wire, works much better for me. It's thin enough to accommodate every bead size, resilient enough to resist bending, pleasantly lightweight, and won't roll away.

I cut off a comfortable section and used a bead spinner to whirl a bunch of beads onto the non-hook end. No need to make a bend in the wire--it's springy and conforms comfortably to the spinner bowl.

I took a pair of pliers and bent the end into a hook thusly:

Notice that the hook is bent quite far, but from the side, it's open enough to slide in the yarn:

It's quite easy to close the gap by bending the main wire towards the hook--no need to pinch it closed. Furthermore, the guitar wire has several advantages over the other methods. First of all, like the beading wire, the guitar string can be hooked directly onto your knitting:

Because there's a slight bulge at the hook end, beads won't fall off that end:

Making stoppers for the other end is simple. Use a sharp matte knife, cut a few slices from an eraser stick. Then poke a hole through each one with a thickish sewing needle and just slide it onto the wire:

Both the Beadle and this thing (the Fleeger? The Bleeger? The Bleegle? The FleegleBeadle? The Guitar-Wire-with-Hook-and-Stopper? ) store nicely in thick plastic straws.

.